The threat of terrorism, specifically active shooter and complex coordinated attacks, is a concern for the fire and emergency service. An attack in public areas, such as schools, shopping malls, churches or any locations where people congregate, is a serious threat to maintaining a strong sense of security and the daily lives of the public.

An active shooter incident is an event involving one or more suspects who participate in an ongoing, random, or systematic shooting spree, demonstrating the intent to harm others with the objective of mass murder, while a complex coordinated terrorist attack utilizes multiple modes of attack in multiple locations to overwhelm the emergency response system. Often active shooter and complex coordinated attacks involve other tactics such as improvised explosive devices (IEDs), vehicle as a weapon and fire as a weapon to augment the attack.

Given the recent spate of what has become known as “active shooter” scenarios unfolding across the nation, fire, EMS and law enforcement agencies, regardless of size or capacity, must find ways to marshal appropriate and effective responses to these incidents. Therefore, local jurisdictions should build sufficient public safety resources to deal with these incidents.

NFPA 3000 Standard for Preparedness and Response to Active Shooter and/or Hostile Events provides jurisdictions a roadmap for communities to prepare for these events. Jurisdictions are encouraged to utilize this groundbreaking standard to educate partner agencies and the community on model practices. Many of those practices have been advocated by the IAFC previously.

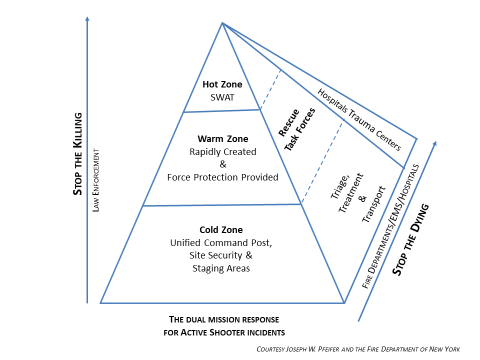

As recommended in NFPA 3000, it is imperative that local fire, EMS and law enforcement agencies have common tactics, common communications capabilities and a common lexicon for seamless, integrated operations. Local fire, EMS and law enforcement agencies should establish standard operating procedures to define each discipline’s role to “stop the killing, stop the dying”.

Standard operating procedures should include at minimum the following objectives:

- Use of the National Incident Management System (NIMS) in particular the Incident Command System (ICS). In accordance with NIMS guidance, fire, EMS and law enforcement should establish a Unified Command (UC) at a co-located Command Post (CP). This requires regular joint training in ICS and UC as well as tabletop and full-scale exercises.

- Fire, EMS and law enforcement agencies should train together. Initial and ongoing training and practice are imperative to successful operations.

- Agencies involved should use common communications terminology. Fire and EMS personnel must understand common law enforcement terms, such as Cleared, Secured, Cover, Concealment, Hot Zone/Warm Zone/Cold Zone and other related terms (red, green etc.).

- Provide appropriate protective gear to personnel exposed to risks. Firefighters and EMS personnel should be provided the appropriate level of ballistic protection specified in NFPA 3000 and NFPA 1500, if they are to participate in warm zone operations as part of a Rescue Task Force or in hot zone operations as a Tactical Medic.

- Consider secondary devices at the primary incident scene and secondary scenes in close proximity to the primary incident scene. Acts of terror using IEDs, as well as active shooters often prepare or actually begin their attacks at a location separate from the area designated as the primary incident scene.

- For incidents involving IEDs, consider fire hazards secondary to the initial blast. For example, in public areas such as restaurants, clubs, schools and churches, natural gas is used in food preparation and heating; therefore, responders should check to ensure that gas lines and valves have not been compromised. Also, be aware that chemical agents may have been deployed to slow the response; therefore, respiratory protection should be considered as part of the PPE for responders.

- Early consideration of the logistical side of EMS units flowing to and from the scene using techniques such as transportation corridors and how fire units can assist in the process.

The IAFC encourages fire departments to utilize the Rescue Task Force or other warm zone techniques when planning the response to an active shooter. A Rescue Task Force (RTF) is a team deployed to provide point-of-wound care to victims where there is an on-going ballistic or explosive threat. These teams treat, stabilize, and remove the injured in a rapid manner, while wearing Ballistic Protective Equipment (BPE) and under the protection of law enforcement officers.

Prior to deploying an RTF, the fire, EMS and law enforcement UC should consider IEDs or other threats such as fire as a weapon. Threat zones must also be identified by the UC. Threat zones include the following.

- Hot Zone - Area where there is a known hazard or direct and immediate life threat (i.e., any uncontrolled area where an active assailant could directly engage an RTF). RTFs should not be deployed into hot zones.

- Warm Zone - Area of indirect threat (i.e., an area where law enforcement has either cleared or isolated the threat to a level of minimal or mitigated risk). This area can be considered clear but not secure. The RTF will deploy in this area, with security, to treat and remove victims and establish casualty collection points, as warranted.

- Cold Zone - Area where there is little or no threat, due to geographic distance from the threat or the area has been secured by law enforcement (i.e., the area where fire/EMS may stage to triage, treat, and transport victims once removed from the warm zone).

An RTF should only be deployed upon agreement of the unified fire/EMS/law enforcement command. Ideally, RTFs will consist of a minimum of two firefighter/EMTs or paramedics and a minimum of two law enforcement officers to provide security. The UC should establish an accountability process for all incident responders using a check-in/check-out procedure. Fire and EMS responders should not self-deploy into the warm zone.

When teams make entry, they should treat the injured using Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC) guidelines. Any victim who can ambulate without assistance should be directed by the team to self-evacuate via a cleared pathway under law enforcement direction. Any fatalities should be clearly marked to allow for easy identification and to avoid repeated evaluations by additional RTFs. Responders should avoid disturbing fatalities when possible to aid in the crime scene investigation.

The RTF can be deployed for victim treatment, victim removal from warm to cold zone, movement of supplies from cold to warm zone, and any other duties deemed necessary to accomplish the overall mission. RTFs should work within law enforcement security at all times.

To sustain skills and readiness, RTF skills and operations should be taught annually and practiced regularly.

RTF initial and ongoing training for all EMS providers should include TECC guidelines and practical skills applications.

Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC)

The TECC guidelines are the civilian counterpart to the U.S. military’s Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines. The TCCC guidelines were developed for military personnel providing medical care for the wounded during combat operations. These guidelines have proven extraordinarily effective in saving lives on the battlefield, and thus provide the foundation for TECC. The TECC takes into account the specific nuances of civilian first responders and the diverse medical needs of non-military casualties. More information on TECC can be found at http://www.c-tecc.org/.

The specifics of casualty care in the tactical setting will depend on the tactical situation, the injuries sustained, the knowledge and skills of the first responders, and the medical equipment at hand. TECC provides a framework to prioritize medical care while accounting for on-going high-risk operations and focuses primarily on the intrinsic tactical variables of ballistic and penetrating trauma compounded by prolonged evacuation times. The principle mandate of TECC is the critical execution of the right interventions at the right time.

TECC is applied in three phases — direct threat, indirect threat, and evacuation care —as defined by the dynamic relationship between the provider and the threat. Indirect threat care is rendered once the casualty is no longer under a direct and immediate threat (i.e., warm zone). Medical equipment is limited to that carried into the field by RTF personnel and typically includes tourniquets, pressure dressings, hemostatic agents, occlusive chest seals and adjunct airways.

Tactical EMS (or Tactical Medic) Differs from the RTF Concept

Tactical EMS is not routine EMS. Tactical EMS — or Tactical Medic — refers to a select EMS provider assigned to a SWAT or similar specialized tactical law enforcement team. Tactical EMS requires the medic to be trained and equipped with the special skills necessary to support these law enforcement teams. Tactical medics should be members of agencies such as fire departments or EMS services who are specifically chosen and trained to be part of the tactical law enforcement team to provide medical care for the law enforcement team. They are not typically used to treat victims until the threat has been neutralized. In contrast, RTF responders come from the cadre of firefighter/EMTs and paramedics who respond daily to calls for help and should not be confused with tactical medics.

Community Preparedness

Fire departments should work with local EMS and law enforcement agencies to prepare for active shooter incidents. Fire chiefs are encouraged to develop plans for mass casualty incidents that include all stakeholders: fire, EMS, law enforcement; federal, state, tribal/territorial partners (including the Federal Bureau of Investigation); hospitals/public health; commercial/building owners (mall, movie theater owners, church leaders; school principals, etc.); and the jurisdiction’s political leadership to have plans in place for an active shooter incident. Facility specific plans should be developed for high-risk locations.

Fire departments should also work with EMS and law enforcement agencies to train the civilian population to take appropriate protective steps by using the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s “Run, Hide, Fight” training or other nationally recognized training, and to help provide lifesaving aid through “Stop the Bleed” training.

Submitted by the IAFC Terrorism and Homeland Security Committee

Adopted by IAFC Board of Directors: 17 March 2018

Download: Active Violence and Mass Casualty Terrorist Incidents (pdf)